A Fine Line: Restoring Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper

November 20, 2025

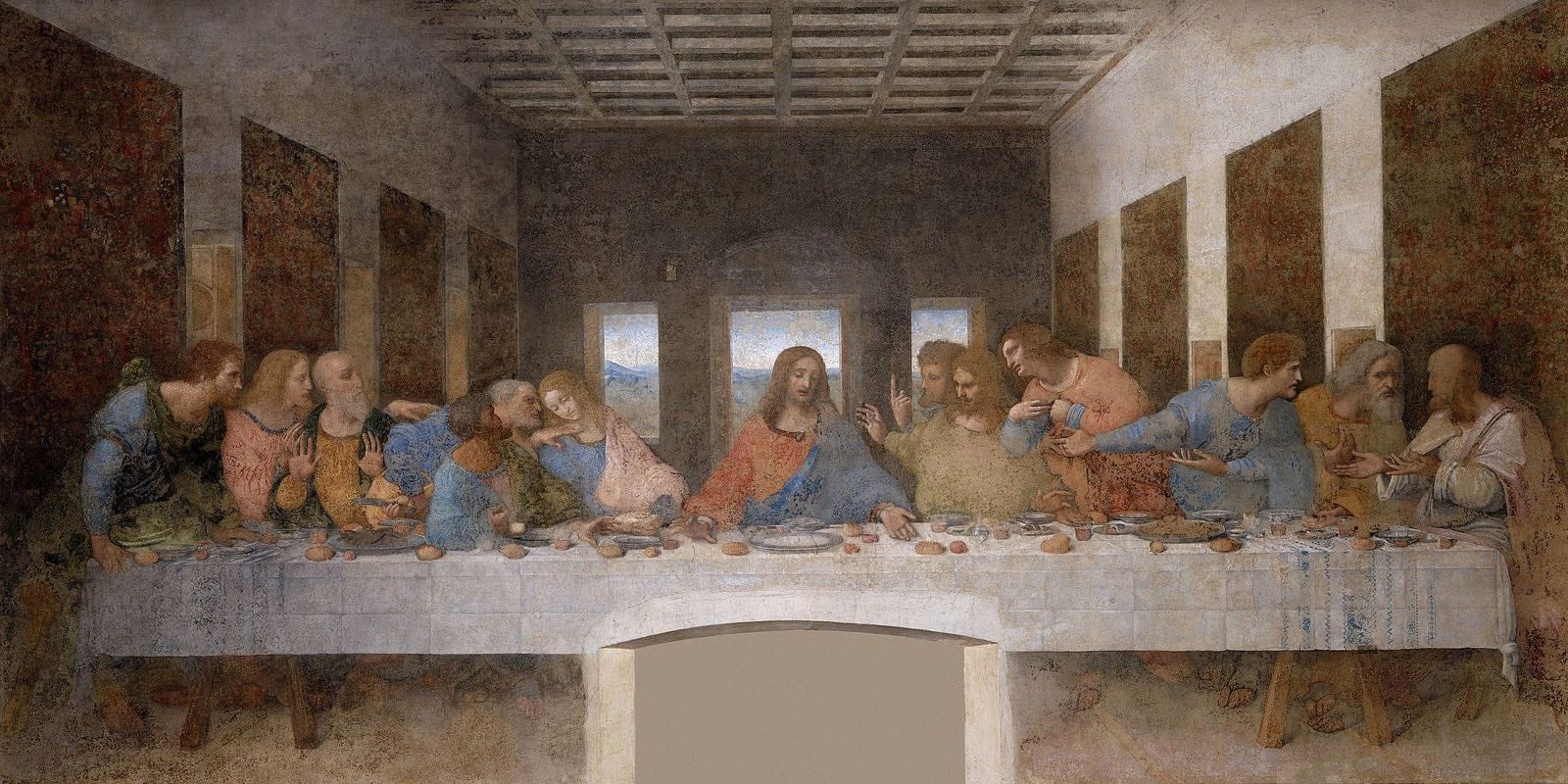

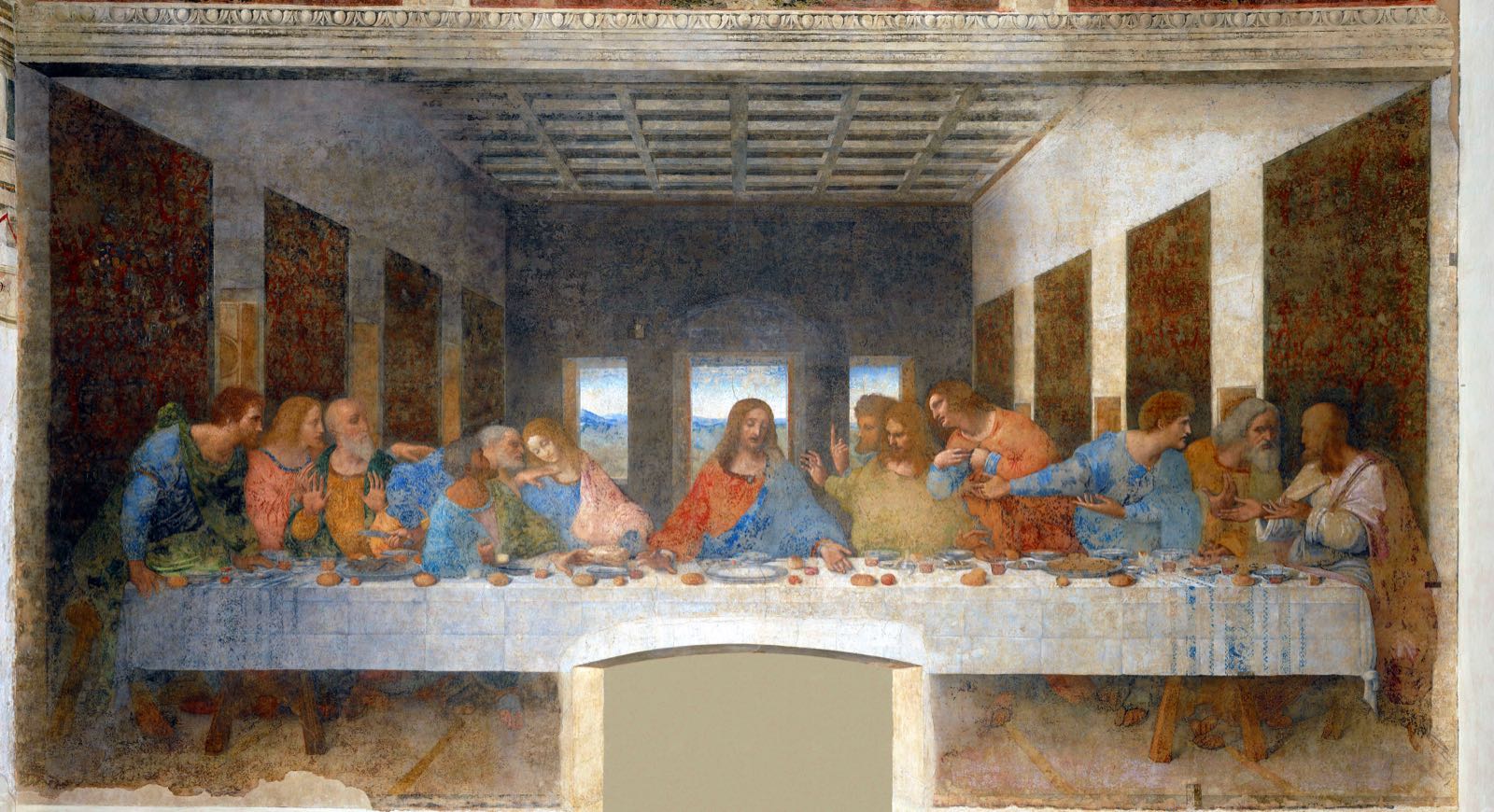

Leonardo da Vinci began painting The Last Supper in 1495, and over five hundred years later it has become one of the most prolific paintings in history. Tickets to see it are treated like gold-dust, and for good reason. Full of symbolism, secrets and speculation, The Last Supper is a painting with a violent, and rich past. But along with conspiracy theories surrounding Judas’ depiction, spilled salt and whether or not Mary Magdalene is present among the apostles, a more pressing concern takes centre stage: The efforts to restore the quickly disintegrating masterpiece.

Leonardo da Vinci was commissioned to paint The Last Supper at the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery by Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. The Duke intended for the church to become the Sforza family mausoleum. Da Vinci, however, had much bigger aspirations for this piece. Yet to paint the Mona Lisa, by 1495 da Vinci had showcased his skill with works such as Portrait of an Unknown Woman and The Virgin of the Rocks. He had built up quite the reputation – but for all the wrong reasons.

Da Vinci consistently failed to deliver commissions on time and often, failed to deliver them at all. The praise his artistic skill had earned him was quickly being replaced with sneers and jokes at his expense. His peers were even suggesting that he was no longer able to finish a painting. A grand biblical scene which depicted the final supper before Jesus was betrayed was just the opportunity he needed to showcase his skill. So with Sforza’s commission, Leonardo set out to save his name.

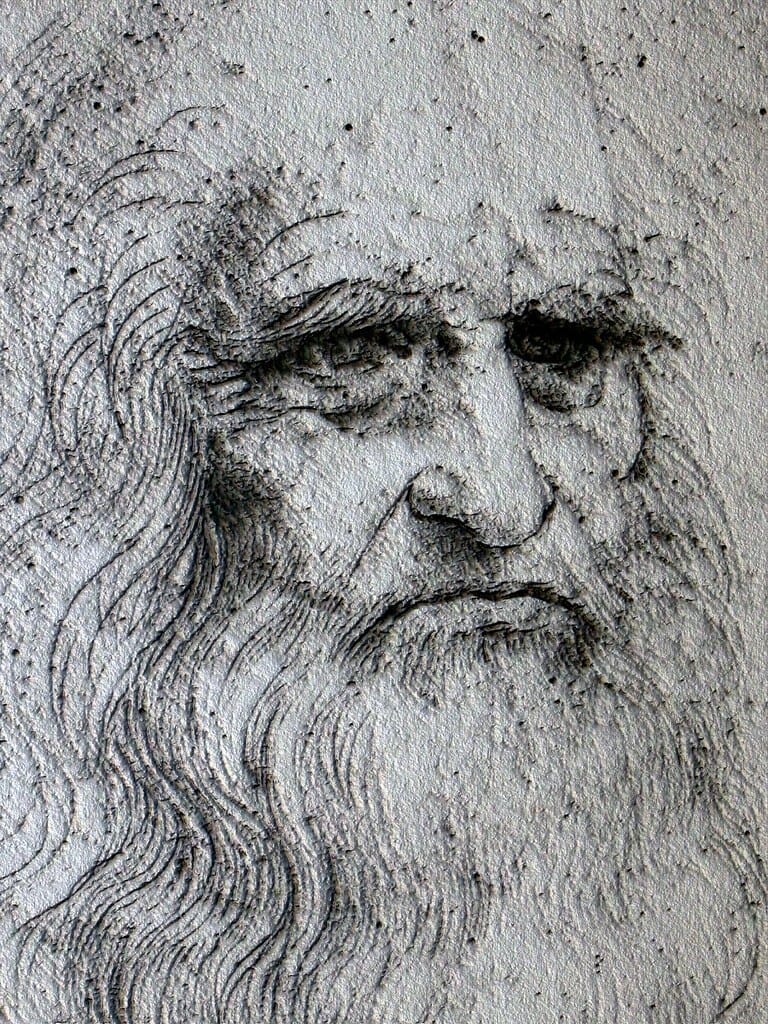

Presumed self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci. Public domain photo via Wikicommons

Table of Contents

ToggleThe disintegration of a masterpiece

Ever the innovator, it’s not surprising that Leonardo wasn’t content to play by the rules when he began painting The Last Supper. Unfortunately, this led to many of the problems we face in preserving the masterpiece. Traditional fresco methods used during the Renaissance focused on applying wet plaster to the wall. This required the painter to work fast, preferably with a pre-set plan of how the piece would turn out.

With little experience painting on a surface this big or with traditional fresco techniques, Leonardo decided instead to experiment with a method that would allow him to work at his own pace. He used paint tempura, mixed with egg, oils and other binding agents and applied this to dry wall. This let him work on the painting for a longer period of time – a total of three years spanning from 1495 to 1498.

It was a risky experiment and one that proved disastrous. By 1517, less than 20 years since the The Last Supper was completed, the paint began to flake away from the wall, while records from 1582 state that by then it was “in a state of total ruin”.

However, Leonardo’s experimental techniques weren’t the only thing to blame for the painting’s failure to stand the test of time. The location of the painting in the Santa Maria church wasn’t exactly an ideal spot for a masterpiece. Exposed to a naturally damp environment with constant flooding, the painting was also located in a room that was close to the kitchen and was constantly subjected to steam and smoke from the ovens for the earlier period of its existence.

Photo of the Last Supper from WikiCommons

Planning a visit to The Last Supper? Check out our detailed guide on tickets, times and other sights to see in Milan.

You might also like: The Art-Lover’s Guide to Pompeii

Want to see the masterpiece before it’s gone for good? Try the Best of Milan tour – which includes a visit to the iconic Last Supper along with other stops around Milan.

Preservation or restoration?

As it stands, some scholars estimate that less than half of the painting is Leonardo’s original work. While a small portion of it has been irrevocably lost, the remainder is the work of restoration efforts that have tried to recreate Leonardo’s work through the ages. Unfortunately these efforts weren’t always successful, and have caused many arguments over how much of the work is by da Vinci’s own hand.

As far back as the nineteenth century Charles Dickens voiced his criticism at restoration attempts when he viewed The Last Supper in 1845. He remarked that, “apart from the damage it has sustained from damp, decay or neglect, it has been so retouched upon, and repainted, and that, so clumsily, that many of the heads are, now, positive deformities”. The dramatist reacted, well, dramatically. However, much of the debate that exists today is based on later restoration attempts.

In a dire state of neglect and disrepair, in 1978 Italian authorities decided to embark upon a major restoration of the painting. There were two main aims for this project: one was to protect the painting from further wear and tear, the other was to restore da Vinci’s original work and strip away years of built up grime, dirt as well as the historic efforts at reconstructing it. Art restorer Pinin Brambilla Barcilon accepted the epic task and embarked on a twenty year project to restore The Last Supper.

Pinin’s work consisted of a deep, yet careful clean of the painting’s surface using specialised strips dipped in solvents which removed layers of built up grime. Next, she and her team of specialists embarked on the task of filling in parts of the painting that had been lost. Using an easily reversible technique, they used faded water colours so that Leonardo’s original work would be easily distinguishable from that of the restoration.

The result? More vivid colours, a cleaner picture and a clear disambiguation between what is left of the original and what has been added for a more complete representation of the painting.

Whether or not the work maintains all of the original brush-strokes of Leonardo’s hand, the fact that five hundred years later painting is as well preserved as it is – despite mould, flooding, and bombings – is nothing short of a miracle.

You might also enjoy: 8 Fascinating Facts you Didn’t Know about da Vinci’s Last Supper

Church and Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan

FAQs – The Last Supper

When and where can I see The Last Supper in Milan?

The Last Supper is housed in the Cenacolo Vinciano, located inside the former dining hall of the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery in Milan. Viewings are extremely limited — typically allowing only small groups every 15 minutes — so tickets often sell out weeks or even months in advance. It’s best to book as early as possible, especially during peak seasons or weekends.

What other major artworks or sites should I visit nearby?

After viewing The Last Supper, you’re already close to several remarkable Milanese landmarks. Highlights include the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie itself, a UNESCO World Heritage Site; the Castello Sforzesco with its museums and Michelangelo’s unfinished Rondanini Pietà; and the Pinacoteca di Brera, one of Italy’s most prestigious art galleries. These sites pair perfectly with a morning or afternoon dedicated to Leonardo’s masterpiece.

How long should I plan for the visit, and are there any visitor tips?

While the viewing itself usually lasts 15 minutes, plan at least an hour for check-in, security procedures, and time to explore the surrounding area. Temperatures inside the refectory are kept cool to protect the painting, so bring an extra layer. Photography rules vary but often restrict flash use. To enrich the experience, consider joining a guided tour that explains the symbolism, historic damage, and restoration work — details that are easy to miss without expert insight.

If seeing The Last Supper has sparked your curiosity, why not take the experience even further? Walks of Italy offers expert-led tours that not only secure your entry but also bring Leonardo’s masterpiece, and Milan’s rich history, vividly to life. With knowledgeable guides, small groups, and seamless organisation, it’s the best way to appreciate every hidden detail and story behind this iconic work.

Explore Walks of Italy’s Best of Milan tour and reserve your spot today for an unforgettable journey into Italy’s artistic heart.

by Aoife Bradshaw

View more by Aoife ›Book a Tour

Pristine Sistine - The Chapel at its Best

€89

1794 reviews

Premium Colosseum Tour with Roman Forum Palatine Hill

€56

850 reviews

Pasta-Making Class: Cook, Dine Drink Wine with a Local Chef

€64

121 reviews

Crypts, Bones Catacombs: Underground Tour of Rome

€69

401 reviews

VIP Doge's Palace Secret Passages Tour

€79

18 reviews

Legendary Venice: St. Mark's Basilica, Terrace Doge's Palace

€69

286 reviews