Pompeii Art Guide: Scandalous Frescoes & Mythic Retellings

June 25, 2025

Few things could be as fascinating to the historically minded as Pompeii.

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, it froze an entire society in time—its streets, homes, and public spaces remarkably preserved. Among its most compelling treasures are the frescoes, mosaics, sculptures, and everyday decorative objects that adorn its ruins. This remarkable collection of Pompeii art not only displays a technical brilliance and aesthetic sophistication but also reveals the intimate details of daily life of an ancient era. As archaeologists continue to uncover new wonders, Pompeii’s art remains a vivid testament to the enduring power of human creativity.

This ancient Italian site is really unlike anywhere else in the world. Strolling along the cobbled streets and damaged villas, you can see an amazing amount of vibrant Pompeii frescoes and wall paintings that are still in remarkably good condition. Ready to see them all and learn about their history? Well, come along on our Pompeii art guide.

Exploring the Pompeii frescoes, wall paintings, and mosaics as you wander the streets of Pompeii is truly a one-of-a-kind experience.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe ultimate guide to Pompeii art

From mythic retellings to scandalous frescoes, Pompeii’s art has fascinated archeologists and art historians alike. And for good reason! Art was a vital element of Roman society and can reveal much about its values and traditions.

Of course, though Pompeii is a popular visitor destination, it’s also an active archeological site, meaning new discoveries continue to be found – many of which includes frescoes and artwork. So, from the methods used to the stories told, here’s your ultimate guide to the magnificent art frozen in time in Pompeii.

It’s amazing that the colors used in the Pompeii mosaics are still so vibrant.

Why was art so important in Pompeii?

One of the strongest methods of communication in the ancient world, it would be difficult to overemphasise how important art was in Pompeii. Long before filmmaking and photography (or even the good old printing press), paintings were used as the main method by which stories were told and people could learn about history and mythology. The Romans, much like any other ancient civilisation, had a host of myths and legends which were vital to their understanding of themselves, as well as their place in the world at large. So it makes sense mythology is one of the most popular themes in the art discovered at Pompeii.

On a smaller scale, art in Pompeii was, of course, also used for aesthetic and decorative purposes. It helped to turn houses into bona fide status symbols for the Roman elite. Wealthy Romans would invest hugely in commissioning grand frescoes to adorn their walls in order to impress their visitors. In fact, because these Pompeii wall-paintings held such pride of place, the archeologists who discovered the Roman villas often named the houses after the frescoes on display, and this still serves as our way of identifying most of Pompeii’s villas.

The Pompeii frescoes and wall paintings are so vibrant centuries later it really is remarkable to see in person.

Seeing red: Pompeian cinnabar

Anyone who has been lucky enough to visit the ancient Roman town will have noticed the distinctive red pigment used throughout many of the Pompeii frescoes (and if you haven’t visited the city yet, we suggest taking a tour of Pompeii with Walks!). Through extensive study and testing, archeologists have discovered that the distinctive red colour comes from the use of a pigment called cinnabar – a toxic mercury sulphide mineral with a bright red pigment.

Cinnabar was commonly used in cities throughout Ancient Rome. However, researchers have noted that there is something distinctive about the particular type used in Pompeii frescos and wall paintings. As it turns out, the mineral was ground to a much finer granule when it was used in Pompeii and mixed with liquid to produce a more brilliant shade of red, as opposed to larger grains which produced a duller hue, and were used elsewhere.

Though the ash and dust may have somewhat dulled the original hue, roughly 2,000 years later the pigment remains an impressive testament to the ingenuity of the city’s painters.

Read More: The Wackiest Roman Emperors

Where to find Pompeii Frescos:

Initiation frescoes in the House of the Mysteries

Located just outside of Pompeii, the House of the Mysteries or Villa dei Misteri got its name from the large series of ornate frescoes in the residential section of the building. Often considered the masterpiece of Pompeii, the vivid red in use throughout the fresco is a prime example of the cinnabar used throughout the city.

This Pompeii wall painting is a series of images commonly thought to depict an initiation into an ancient Roman mystery cult – believed to be that of Dionysus (or his Roman equivalent, Bacchus). One of the frescoes at the back of the wall shows the god in the lap of his mortal consort Ariadne, while the rest seem to show a young woman going through the stages of initiation into the cult.

The Cult of Bacchus was somewhat of a hot-topic in Ancient Roman society. The Roman god presided over wine, revelry and dramatics. Although these were all was integral parts of Roman life, the cult gained a reputation for bizarre rituals and frenzied gatherings which posed a challenge to the strict regime governing Roman Society. In fact, in A History Of Rome contemporary Roman historian, Livy, gives a scandalised account of their rituals and practices. He remarked,

“when the wine had enflamed their minds, and the dark night and the intermingling of men and women, young and old, had smothered every feeling of modesty, depravities of every kind began to take place because each person had ready access to whatever perversion his mind was inclined”.

Though his views are acknowledged to be exaggerated, this still provides a fascinating insight into how the cult was perceived during the time.

The rich colours used in Pompeii frescos and wall paintings can be thought of as a representation of the cult’s dynamic and vibrant energy while the life-sized depictions of the subjects have been noted to give a sense of communality to the scene, implicating the viewer into the initiation ritual themselves.

Riot at the Amphitheatre Fresco at The House of Actius Anicetus

Gladiator games weren’t just limited to the Colosseum – though that’s certainly the place to go if you want to walk in the footsteps of Gladiators. The arena in Pompeii actually boasts the title of being the oldest surviving amphitheatre from Ancient Rome (built around 70 BC), and has some fascinating stories of its own to tell.

One of these stories can be found in a Pompeii fresco discovered in The House of Actius Anicetus, depicting a riot that broke out between the people of Pompeii and the citizens of Nuceria in 59CE. Like football games today, gladiatorial games often enflamed town rivalries in Ancient Rome. In this case, the riot not only resulted in maiming, bloodshed, and death but a ban on holding games in Pompeii’s amphitheatre at all for a subsequent 10 years.

What we know of the event comes from an account from Roman senator and historian Tacitus. In The Annals, he remarks,

“About the same time a trifling beginning led to frightful bloodshed between the inhabitants of Nuceria and Pompeii, at a gladiatorial show exhibited by Livineius Regulus, who had been, as I have related, expelled from the Senate. With the unruly spirit of townsfolk, they began with abusive language of each other; then they took up stones and at last weapons, the advantage resting with the populace of Pompeii, where the show was being exhibited”.

While there is some disagreement as to whether the owner of this house was an ex-gladiator or not, it’s certainly interesting that an event which earned Pompeii it’s fair share of reproaches from the senate is depicted so proudly on the walls of this villa.

Read More: 5 Roman Colosseum Facts That are Probably False

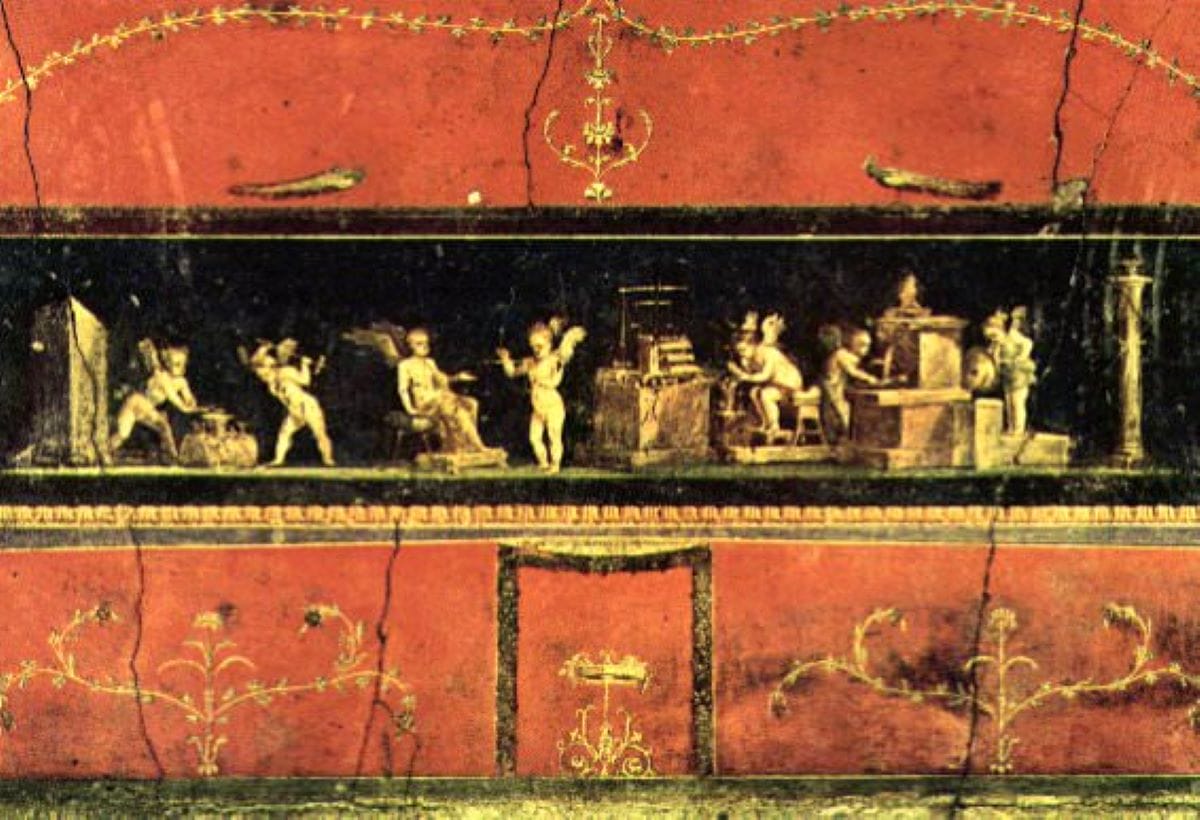

Cupids in the House of the Vettii

The artwork found in Pompeii is just exquisite. Photo credit: WikiCommons

The House of the Vettii is one of the most important villas in Pompeii in terms of artwork. The fresco above comes from the Triclinium – or dinning room – of the villa and displays a series of Cupids performing tasks such as making perfume, and working as goldsmiths, bakers and oil merchants. Of course, as the son of Venus, The Roman goddess of love, and Mars, The Roman god of war, Cupid presided over passion. So it could be that this particular Pompeii fresco is supposed to represent being passionate about one’s work. It’s also notable that a number of these trades are related to the senses which feeds into his symbolic nature as a god of love and desire.

The House of the Vettii is believed to have belonged to two freed brothers (thought to be craftsmen) who bought their way out of slavery. So it’s pretty understandable why they’d place such an emphasis on whistling while you work!

Hercules as a Child in the House of the Vettii

A painting of Hercules as a child found in the Casa dei Vettii. Photo credit: AlMare/WikiCommons

Located in the House of the Vettii, in what archeologists believe to have been either a dining or guest room, this Pompeii fresco of Hercules depicts a famous scene from the hero’s childhood.

The focal point of a number of religious cults, Hercules was widely worshipped throughout Pompeii and was viewed as a protector of the region. He was even heralded as the founder of the neighbouring town Herculaneum, and ironically the town’s destroyer, Mount Vesuvius.

The story goes that Hercules’ mother Queen Alcmene was tricked into sleeping with Jupiter one night when he took on the guise of her husband. When she gave birth to two sons, his mortal parents soon discovered that while one, Iphicles, was the son of her husband (King Amphitryon), the other, Hercules, was the son of the god Jupiter. Jupiter’s wife, Juno, became enraged at her husband’s betrayal. But being King of the gods made Jupiter a difficult target. So Juno took her rage out on the young Hercules instead and sent two snakes to kill him in his crib. However, the demigod child had the strength of 10 men and dispatched them both easily. The legend continues that when Hercules came into adulthood, Juno plagued him with madness which caused him to murder his wife and child. In atonement, he performed the 12 labours – and the rest is, if not history, legendary!

Where to Find Pompeii Mosaics:

Alexander the Great in The House of the Faun

The Alexander Mosaic is one of Pompeii’s most incredible floor mosaics.

Roman appreciation for Greek themes, history and art was significant, and this mosaic of Alexander the Great provides a perfect example of how Greek culture was often repurposed within a Roman context. The elaborate mosaic depicts an epic scene from the Battle of Issus in 333 BC showing Alexander and his army defeating the Persian King Darius. Remembered as one of history’s most iconic names, Alexander conquered a number of nations, instilling them with Greek culture; something the Roman Empire clearly admired and was emulating on a large scale.

It is also notable that Alexander’s breastplate bears the head of the gorgon Medusa from Greek mythology, widely considered a protection spell against evil.

It really is remarkable that Pompeii’s murals and wall paintings are all so vibrant centuries after the eruption.

Pompeii Art FAQs

What are Pompeii frescoes and where can I see them?

Pompeii frescoes are colorful wall paintings created using a plaster technique unique to ancient Rome. You can find some of the best-preserved examples in the Villa of the Mysteries, House of the Faun, and House of the Vettii.

What’s the difference between Pompeii frescoes and Pompeii murals?

“Pompeii frescoes” refers to the technique of painting on wet plaster, while “Pompeii murals” generally describes large, decorative wall scenes—often created using the fresco method. Both terms are frequently used interchangeably.

Are there any famous Pompeii mosaics to see?

Yes! One of the most renowned is the “Alexander Mosaic” from the House of the Faun. Pompeii mosaics often decorated floors and depicted intricate mythological or everyday scenes.

What do Pompeii paintings reveal about ancient Roman life?

Pompeii paintings and wall art give us a vivid look into Roman beliefs, daily activities, mythology, and even fashion. They’re an invaluable window into the ancient world.

Can I visit Pompeii’s art sites on a guided tour?

Absolutely! Many guided tours highlight the most famous frescoes, mosaics, and murals, offering expert insights into their history and meaning.

Of course, the best way to appreciate Pompeii’s stunning art is to go and see it yourself! The best way to do this is in the hands of an expert guide to give you the context behind the pieces, which you can do on our Best of Pompeii Tour. Or take the scenic route with our Pompeii and Amalfi Coast Day Trip from Rome.

by Aoife Bradshaw

View more by Aoife ›Book a Tour

Pristine Sistine - The Chapel at its Best

€89

1794 reviews

Premium Colosseum Tour with Roman Forum Palatine Hill

€56

850 reviews

Pasta-Making Class: Cook, Dine Drink Wine with a Local Chef

€64

121 reviews

Crypts, Bones Catacombs: Underground Tour of Rome

€69

401 reviews

VIP Doge's Palace Secret Passages Tour

€79

18 reviews

Legendary Venice: St. Mark's Basilica, Terrace Doge's Palace

€69

286 reviews