The Life of Leonardo Da Vinci: 9 Facts They Didn’t Teach You in School

June 19, 2023

Painter, writer, inventor, sculptor, musician – Leonardo da Vinci was one of Italy’s original Renaissance men. In fact, the idea of the “Renaissance man” was developed during the very time in which he lived. As one of the foremost intellects of world history, his brilliance survives today in artwork, statues and notebooks found throughout Italy and beyond.

A presumed self portrait of Leonardo Da Vinco. Photo credit: MAMJODHFor all his fame, da Vinci remains a bit of an enigma. He didn’t leave a lot of finished works and early biographical details are scant. What we do know about him paints a picture of immense genius – one of the most prolific minds of his day, if not always one of the most focused. There is a lot that we’ll never know about Leonardo da Vinci, but here are a few of the more interesting things that we do know.

Table of Contents

ToggleThough born a “nobody”, da Vinci’s talent was clear from the start

Leonardo da Vinci was an illegitimate son. His father, a respected lawyer, and his mother, a peasant of the same town, were never married. For reasons that are still somewhat murky, the young boy eventually came to live with his dad. One way or another Leonardo never received the classical education in Greek, Latin and higher mathematics that would have been common to high-born boys of his day.

Despite these handicaps, he showed artistic talent early on, and as a young teenager, he was sent to Florence to work as an apprentice for the Florentine painter Andrea del Verrocchio, where he quickly surpassed his master’s talent.

It’s said that Verrocchio completed his 1475 masterpiece, the Baptism of Christ, with the help of da Vinci, who painted the background and probably the young angel holding Jesus’ robe. After seeing da Vinci’s talent, popular legend has it that Verrocchio vowed to never paint again, though this is one rumor that’s never been proven.

Though officially attributed to Verrocchio, the Baptism of Christ shows da Vinci’s official launch into the art world. Go see it in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery.

Da Vinci was notorious for never finishing his work.

His wide range of interests often distracted him and his perfectionism discouraged him from declaring a painting officially finished. Often accused of being a helpless procrastinator, the problem wasn’t that da Vinci wouldn’t start works, it was that he was constantly starting works and neglecting to finish the ones he had already begun.

The Uffizi houses some of these unfinished masterpieces, including two of the artist’s first paintings, done in collaboration with Verocchio: the Annunciation and the Adoration of the Magi. The first of which was painted in 1472 and housed in the Uffizi since 1867, the latter was left incomplete in 1481 and has been in the Uffizi since 1670.

But these aren’t the only works the artist never officially finished. The list includes St. Jerome in the Wilderness in the Vatican City, the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne held in the Louvre in Paris, and even the great Mona Lisa are examples of the da Vinci masterpieces that the artist never declared completed.

It appears that Leonardo was rarely happy with his work and had trouble stopping himself from making minute adjustments to his paintings long after they were probably “complete”.

He was also an extremely slow worker

Da Vinci spent three years working on the Adoration of the Magi and yet it still remains unfinished. Public domain photo via Wikicommons

Da Vinci might have gotten away with not finishing a few works if he had maintained a faster pace. In his lifetime Van Gogh painted more than 2,000 works. Da Vinci, in comparison, spent more than three years painting the Last Supper and more than five years working on the Mona Lisa. The Adoration of the Magi took another three years, and, yes, it too, remains unfinished!

Da Vinci dissected more cadavers than many contemporary doctors

There’s a reason da Vinci painted the human form so realistically: the artist obsessively studied human anatomy by dissecting human cadavers. In an era when medical knowledge in Europe was rudimentary, to say the least, da Vinci was one of the original pioneers in the field of documenting the human anatomy. To this day, he is considered one of the forefathers of the study.

We can see da Vinci’s vast knowledge of human anatomy in another unfinished masterpiece, St. Jerome in the Wilderness. Hanging in the Vatican Museums, it shows Saint Jerome kneeling under a crucifix. He is in a rocky landscape and the hermetic saint’s tamed lion lies at his feet. Painted in 1480, the incredible detail of St. Jerome’s neck and the bulging tendons and muscles of his shoulders give away da Vinci’s burgeoning obsession with anatomy and close attention to human physiology. His study of the human body through secret dissections had likely already begun.

At first, the artist likely had to dissect largely in secret. Though dissection itself wasn’t technically illegal, Leonardo had a tough time getting bodies. But as his reputation grew, cadavers became easier to come by, and by 1517 da Vinci is reported to have completed more than 30 dissections.

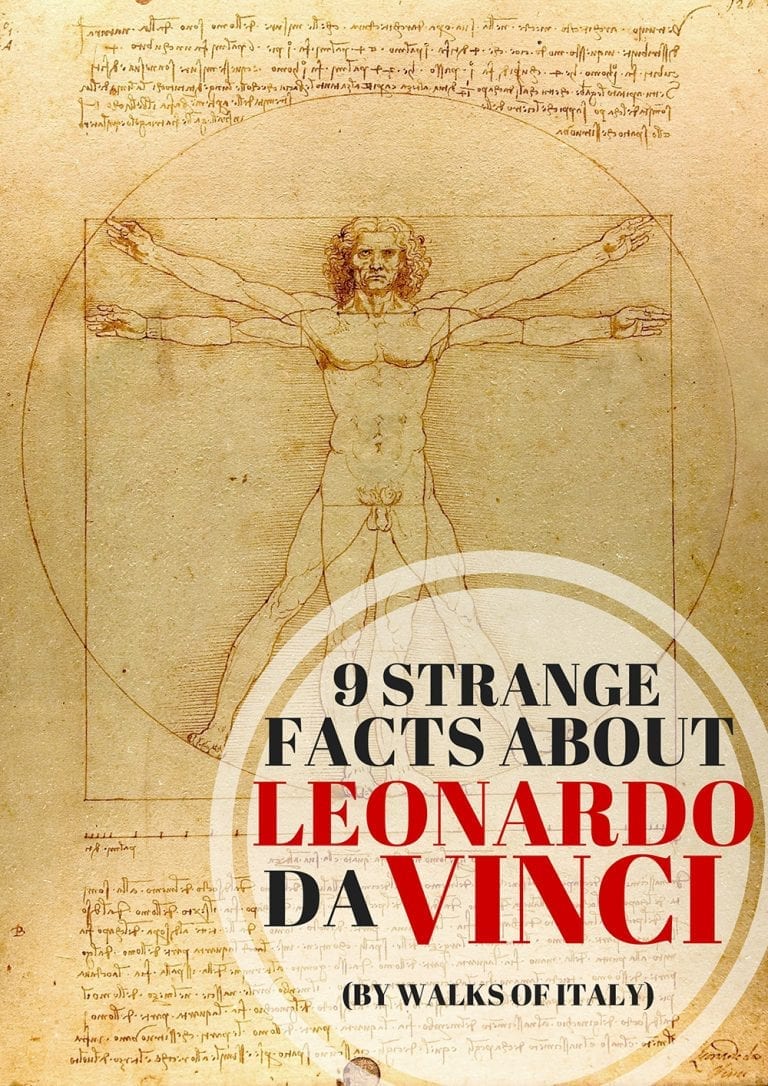

His most celebrated sketch on human anatomy is hidden away and extremely difficult to see.

During his career, da Vinci filled dozens of notebooks with his thoughts, equations, illustrations, experiments and scientific/anatomic observations. The most famous of these sketches is the Vitruvian Man, a study in classical proportions that was never meant to be made public. Drawn in one of the artist’s private notebooks around 1490, the sketch was a way for da Vinci to ponder the “ideal” human proportions proposed by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. The drawing has come to symbolize the image of the Renaissance man as a whole – a person perfectly in proportion with the world around him.

Though many have seen recreations and reprints of the sketch, the original Vitruvian Man rarely sees the light of day. The drawing is kept in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, but it’s too fragile to be on permanent display. These days, it’s only brought out on very special occasions. The Vitruvian Man was last on display in an exhibition in 2013 – it was the first time anyone had seen the sketch in 30 years!

The Last Supper owes some of its creation to a sodomy charge against Da Vinci.

Most scholars believe that da Vinci was a homosexual due to his penchant for surrounding himself with young men, though some believe he was bisexual. Sigmund Freud even published an essay in 1910 that came to the conclusion that he was gay, but sublimated all his sexual urges into art and research. Whatever the case may have been, he seems to have enjoyed the occasional liaisons with men and he was publicly accused of sodomy in 1476. Though the charges were dropped, the case nonetheless scared the artist – sodomy was punishable by death in Renaissance Florence – and he quickly fled Florence for Milan. While there he worked for the ruling Sforza family as an engineer, painter, party planner, and sculptor.

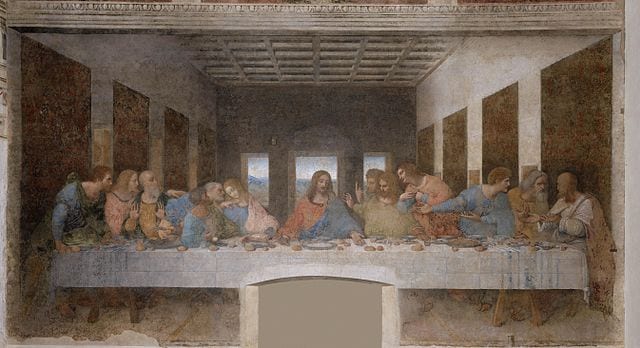

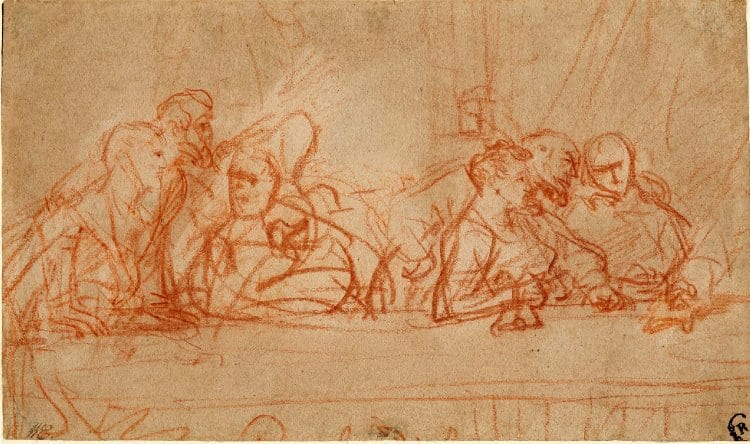

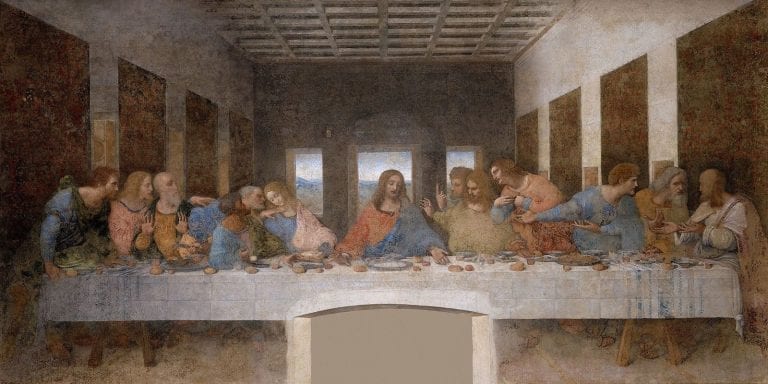

His masterpiece in Milan should have been the largest equestrian statue ever made, in honor of the Duke, Francesco Sforza. But true to form, he only got as far as creating a 24-foot clay model before a series of wars saw the bronze he had been allocated used for cannon balls by the Milanese and the model used for target practice by invading French soldiers. Luckily, he did finish arguably the world’s most famous fresco: the Last Supper. Located on a cafeteria wall of the Dominican convent attached to the beautiful Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, the fresco was deemed an instant masterpiece but it was also fraught with problems. The foremost of which was that da Vinci’s remarkably slow process meant a normal quick-drying fresco technique (in which paint is applied to plaster that is still wet) simply would not work. Instead, the ever-experimental artists developed a new fresco technique in which he painted directly onto a dry wall.

The Last Supper was, in one very important aspect, a colossal failure.

Da Vinci’s new technique was called secco or “dry”, and though it looked good, and was more suited to his slower pace, it wasn’t made to last. The problem was that the paint didn’t bond to the wall in the same way that it would have if it had been painted onto wet plaster. As a result, the Last Supper began to deteriorate almost immediately. Throughout the years, the painting has also suffered damage from a variety of, uh, acts of God? For instance, the bottom of the painting was destroyed when a door was added in the middle of the wall and the wall itself narrowly avoided destruction after a WWII bomb destroyed nearly all of Santa Maria delle Grazie, including the cafeteria surrounding the wall.

Today, the painting has been restored, the room is kept at a suitable temperature to avoid further deterioration and only 25 people are able to view the fresco in 15-minute intervals. The paint is still deteriorating, though, so see it as soon as you can and be sure to book your tickets ahead of time, or better yet, take a guided tour for a hassle-free visit with an art historian guide.

Da Vinci likely saw himself first and foremost as an inventor

Though we often think of da Vinci as a painter, he actually only produced about 20 paintings in his lifetime – which is one reason why they are so famous and highly valued. In fact, da Vinci seems to have felt most at home in his role as an inventor and engineer.

Due to internecine warfare during the Renaissance, there was a high need for military engineers during da Vinci’s life, and he was lucky to get a job with the Sforza family. While working for them he was expected to design weapons and other military necessities while also being allowed to sculpt and paint. He worked this way, as the Duke’s military engineer, for 17 years.

For da Vinci, there was no separation between art and science, and his wide-ranging skills allowed him to create new mechanical ideas then draw them well enough to create blueprints used for generations to come.

Modern-day models of some of these ancient machines can be found at the National Science and Technology Museum Leonardo da Vinci, in Milan. The museum is dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci as a “symbol of the continuity between scientific-technological and artistic culture.”

Originally founded with a collection of models reconstructed from da Vinci’s drawings of various machines, today the collection has grown to include multiple interactive exhibits allowing guests to play with the da Vinci’s various inventions. Also on display are videos and 130 models of his inventions, including early tanks, water-going vehicles, and flying machines. The museum gives life to the artist’s true loves: invention and engineering.

The Mona Lisa may be da Vinci’s most mysterious work.

Not all of Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpieces are found in Italy. The magnificent Mona Lisa, or La Gioconda as it’s known in Italian, is kept in the Louvre Museum in Paris, France.

The Mona Lisa was started in Italy, but finished on French soil after the artist was offered the title “Premier Painter and Engineer and Architect to the King” by Francis I. The new job allowed him to live a life of leisure in an ample country manor house, but it’s said the artist was never pleased to be away from Italy. Despite any misgivings, he died in Clos-Lucé, France in 1519 at 67 years old.

There are dozens of myths, legends, rumors and lies swirling around the Mona Lisa – that da Vinci was sleeping with the subject of the portrait, that her smile is because she’s pregnant, that it was da Vinci’s absolute favorite painting, that ‘she’ was in fact modeled after a he…the list goes on and on. for the most part, the rumors are impossible to prove or disprove. We do know the artist kept the painting with him after it was officially finished and continued to add details and brushstrokes here and there for the rest of his life.

Whether it was da Vinci’s favorite or not, it is certainly the world’s favorite: The Mona Lisa is regarded as the best known, most reproduced, and most talked about work in all of Leonardo da Vinci’s incredible portfolio!

Read more: 8 Fascinating Facts You Didn’t Know About Da Vinci’s Last Supper

Update notice: This article was updated on April 12, 2023.

by Gina Mussio

View more by Gina ›Book a Tour

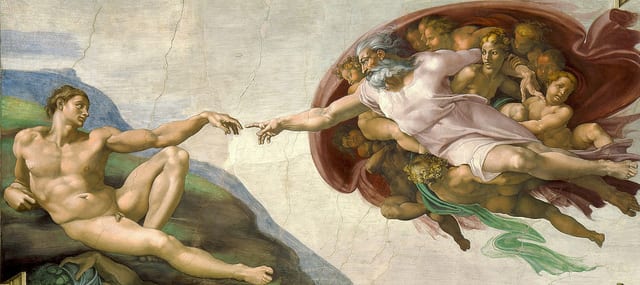

Pristine Sistine - The Chapel at its Best

€89

1794 reviews

Premium Colosseum Tour with Roman Forum Palatine Hill

€56

850 reviews

Pasta-Making Class: Cook, Dine Drink Wine with a Local Chef

€64

121 reviews

Crypts, Bones Catacombs: Underground Tour of Rome

€69

401 reviews

VIP Doge's Palace Secret Passages Tour

€79

18 reviews

Legendary Venice: St. Mark's Basilica, Terrace Doge's Palace

€69

286 reviews