13 Things to See at the Louvre: Lamassu, Venus de Milo, & More

April 22, 2025

The Louvre is not only one of the best art museums in the world, it’s also one of the biggest. If you’ve ever tried to see it by yourself, you know that it can be extremely daunting to find your way around, see what you want to see, and well, not buckle under the weight of so many masterworks under the same roof.

There are 35,000 objects on display out of a collection of 380,000 so as much as we hate to say it, seeing it all in one visit is simply not an option.

But there is definitely a short list of artworks that you shouldn’t miss. Step inside the Louvre with our insider guide to the museum’s 13 must-see exhibits. From the iconic Venus de Milo and the controversial pyramid to the museum’s lesser-known gems, get ready for a journey through art and history.

This beautiful, yet controversial pyramid conceals some of the world’s most impressive art collections underneath.

13 Things to See at the Louvre – From Venus de Milo to Hidden Gems

Almost all major cities have impressive museums, but the Louvre is definitely in a league of its own. From the most famous portrait in the world to little-known marble statues that will blow your mind, the Louvre’s must-sees are seemingly infinite.

But don’t worry, we’ve compiled a Louvre Highlights Guide to set you on the path to see all of the museum’s most important works.

Must-See Highlights at the Louvre

1. The Winged Victory of Samothrace

When is an old marble statue not just another old marble statue? When it’s one of the oldest and most influential statues in the world. If you have ever been to an art museum anywhere, you have definitely seen more than one classical figure chiseled from stone in the Greek style by an ancient hand.

What you probably don’t know is that the vast majority of those statues are copies made by Romans of Greek originals. Not only are these original greek statues much older than their Roman copies – often by hundreds of years – they are also much, much rarer.

Only a fraction have survived to the present day and the Winged Victory of Samothrace is perhaps the best of the bunch. Although we don’t know the sculptor, the technical mastery of the work as well as the way it imagines elements around it (like the wind ruffling the Victory’s dress) have made it one of the single most influential sculptures in the history of Western art. Not bad for a lady who is 2,200 years old and counting.

Insider’s tip: If you are short on time, but really want to explore the Louvre’s must-sees, consider taking our Skip-the-Line Louvre Highlights Tour. A local guide will lead you to the Mona Lisa, Venus de Milo, the Crown Jewels, and more amazing hidden gems found in the Louvre’s enormous art collection in just two hours.

2. Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss

The love story between Psyche and Cupid – yes, the little, winged boy with the love arrows, but grown up – is one of the great classical romances, capable of pulling at the heart strings of classists and normal folk alike. This statue by Antonio Canova, one of the last of the era-defining Italians, captures the most poignant moment of the story with immense tenderness.

Despite the fact that Canova, who was a favorite of Napoleon, coaxed the two characters from cold marble, the work pulses with both romance and intense eroticism. It also demonstrates a surprisingly pleasant way to kiss someone.

3. The Timeless Beauty of Venus de Milo

No arms? No problem. The Venus de Milo is one of the most famous classical depictions of female beauty. Along with the Mona Lisa and Michelangelo’s David, this is probably the most recognized piece of art in the world.

Venus de Milo facts:

- Its age (over 2,000 years) beauty, and iconic missing arms have all combined to make it one of the most enduring representations of classical female beauty in existence.

- The French also helped things along; since acquiring the statue from the Greek island of Melos (or Milo, in French) in 1821, they have promoted the heck out of it. They even caused a scandal in the art world by covering up its Hellenistic origins in order to claim that it was older, and therefore more valuable, as it was believed at the time that Classical art was of a higher order than Hellenistic art.

- Even if it is a few hundred years younger than some French scholars were originally willing to claim, today the Venus is one of the few works of art that still inspires a transcendental awe among many who view it.

4. The Raft of the Medusa

If the saying “worse things happen at sea” could be traced back to a single incident, the wreck of the Medusa would be a very strong candidate.

Due to poor navigation, this French frigate wrecked off the coast of Mauritius and 151 of the 400 sailors on board ended up adrift on an improvised raft with a lot of wine but very little food and water. Heaving drinking, murder, mutiny, and cannibalism ensued. When help finally arrived, only 15 of the original 151 were left alive.

The only good thing – if you can call it that – to come out of the whole affair was a painting by Theodore Gericault that helped to define the French Romanticism movement called the Raft of the Medusa. Aside from being a simply jaw-dropping work, its creation marked a seismic shift from the idealized (some might say “stiff”) themes favored by Neo-classicism to the more dramatic and emotional subjects of Romanticism. From a visceral standpoint, it is one of the most shocking things to see at the Louvre and one of the more macabre sights in Paris outside of the Catacombs; a harrowing work that is hard to look at without experiencing a shiver for the poor men aboard the raft.

5. Liberty Leading the People

Chances are, you’ve seen this painting before. It’s the unofficial national painting of France and features the famously bare-breasted female personification of Liberty as she leads fighters during the “July Revolution” of 1830. The popularity of the work when it was first painted turned the female character, aka Marianne, into a symbol of the French Republic and its general antagonism towards monarchies. Make no mistake though – it doesn’t gloss over the harsh realities of France’s struggle for representative government. The broken bodies beneath the triumphant Marianne allude to the 40 years of civil war and political and social upheavals that had rocked the country. At 8 by 10 feet, its scale also matches its sense of dramatic patriotism.

6. The Coronation of Napoleon

Speaking of large paintings, the Coronation of Napoleon is a nearly unbelievable 33 feet by 20 feet. The size is perhaps unsurprising given that it was commissioned by the Little General himself and painted by his official painter, Jacques-Louis David.

It also boasts a similarly, ahem, napoleonesque official name: Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon I and Coronation of the Empress Josephine in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris on 2 December 1804.

In some senses, it’s less a work of art than a sort of Neo-Classical Sargeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover, featuring a who’s who of famous French politicians from the era that includes Napoleon’s Family, a slightly bewildered-looking Turkish diplomat, and of course, the painter himself.

7. Sleeping Hermaphroditus

You might think you’ve seen a lot of works like this before, but trust us, it has quite a twist. What looks, at first glimpse, to be a naked woman reclining on a very soft cushion, is actually…a man…er, well, something in between. In fact, it’s a depiction (a Roman copy of a Hellenistic bronze, if you’re a stickler for details) of the god Hermaphroditus who sported both male and female sexual organs. Originally unearthed in Rome and displayed in the Borghese Gallery, it was sold to the occupying French, and now sits in the Louvre. Hermaphroditus was actually a popular subject of paintings and statuary, even if modern audiences are less comfortable with the topic than the ancient Greeks and Romans were.

The story has one more interesting wrinkle. Take a look at the cushion upon which Hermaphroditus reclines – It wasn’t part of the original. Instead, it was sculpted by none other than the master of Italian Baroque art, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and is widely considered one of the softest-looking cushions ever cut from stone.

8. Hammurabi’s Code

Here’s one that you should remember from your history classes at school. The code of the Ancient Babylonian King Hammurabi, which dates to 1754 B.C., is not only one of the oldest examples of written laws in the world, its one of the oldest readable written texts ever discovered. Most of it is incredibly dry; it is, after all, a code of laws outlining rules pertaining to business transactions, inheritance, divorces, taxes and the like. But it also contains one of the first written examples of the phrase “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” Life in ancient Babylon was not exactly forgiving.

9. I.M. Pei’s Pyramid

When the Chinese American architect, I.M. Pei was commissioned to create a new entrance to the Louvre in 1984 it raised a few eyebrows. When he came up with a giant, Modernist steel and glass pyramid it seemed half of Paris was up in arms. Although the controversy has quietened down over the years and the pyramid has gained many supporters, it remains one of the more divisive structures in the city. What do you think?

Hidden Treasures of the Louvre

Now that we’ve explored some of the museum’s most popular artworks, let’s take a look at some of the Louvre’s lesser-known gems.

10. Lamassu and Other Wonders

Another oldy but very goody, the Lamassu are protective spirits that guarded entrances in ancient Assyria as far back as 3000 B.C. To put that another way, the statues in the picture above would have been older to the ancient Greeks than their Winged Victory statue is to us. If their age alone isn’t enough to wow you, their craftsmanship certainly will. These colossal winged bulls with the heads of men are so perfectly otherworldly, you can stare at them for minutes on end wondering just what type of people could dream them up and carve them from blocks of solid stone. Straddling the line between art and artifact, these massive beasts never fail to quicken the pulses of museum goers.

11. The Dying Slave and the Rebellious Slave

Michelangelo Buonarotti was many things; “content” and “happy” were not among them. Throughout his history-changing career he developed an unparalleled ability to translate pathos, despair, and anguish to the figures he carved from marble – see the Pietá in St. Peter’s Basilica, and his famous statue of David.

Michelangelo has two statues of slaves in the Louvre. Aside from being fantastic examples of his mastery of sculpting the human form and depicting emotions, their creation is part of a fascinating story of artistic frustration. Both statues were originally sculpted to be part of the tomb of Pope Julius II, who also commissioned Michelangelo to paint his famous frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

As you might expect from the guy who made big art projects a signature of his papal legacy, Julius II’s tomb was supposed to be the greatest monument since the Egyptians built the pyramids and Michelangelo’s crowning masterpiece. But after numerous delays and budget cuts that dragged on for years after Julius’ death, the tomb was built in a much-diminished form and many of the pieces that Michelangelo had intended for it were parceled off to various private collections and churches. Although the tomb exists today in Italy and features Michelangelo’s famed sculpture of Moses, it ended up being one of the great disappointments of his career. Whether or not these Slaves show some of Michelangelo’s despair and professional frustration during those years is hard to say, but they are great examples of his ability to coax emotion from his art.

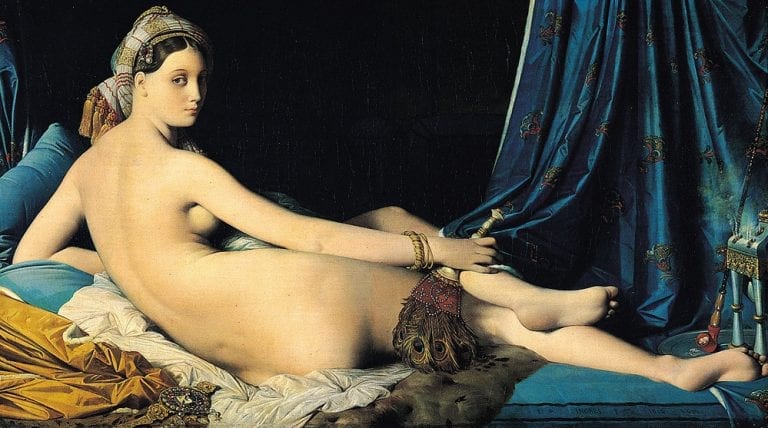

12. Grande Odalisque by Ingres

Most art museums have their fair share of paintings of naked women, but few have been as celebrated or as controversial as Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ Grand Odalisque. When artists talk about “odalisques” they are referring to a figure that was popular in paintings of the Romantic era depicting young women supposedly living in the harems of Eastern Sultans. These figures brimmed with exoticism, eroticism, and the sort of sexual availability that the women of western Europe were thought not to possess.

They were, in other words, a romantic ideal of Eastern sexuality and there is arguably no more idealized version of the odalisque than Ingres’ nude lady who looks suggestively back over her shoulder perfect shoulder while brandishing a fancy feather duster (okay, it’s a fan). He went so far as to elongated her back and stomach by an extra five vertebrae, apparently because he thought it increased her sensuality. Whether you see it as a striking study of female beauty or a problematic example of male desire warping the image of women, it’s a fantastically intriguing work.

13. The One and Only Mona Lisa

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is a painting that hardly needs an introduction, but perhaps a few words on why you should see it – and you definitely should – will whet your appetite for an image that is so ubiquitous it often seems a little commonplace. The Mona Lisa is not the most artistically accomplished painting in Louvre, nor the most beautiful, it’s not the most emotive or even the most awe inspiring. What it has, more than perhaps any other work in the world, is a rare combination of technical mastery, new artistic techniques, provenance to a celebrity artist, and a very interesting history.

Da Vinci was famous even in his own day as a genius and a polymath who was literally changing the world. Because only a handful of his paintings survive each one has an outsized importance as the work of a man whose name was and is a bi-word for genius. He painted the Mona Lisa with a technique of his own devising called “sfumato” in which he layered coats of semi-transparent paint washes one on top of another to create a sense of three dimensions using light and dark. At the time it was revolutionary and so he was creating images that literally no one else on earth could create.

It really does feel as if she is looking right at you.

Read more: Why Did They Move the Mona Lisa? (Plus Other Fascinating Facts About the Famous Painting)

And what an image. Mona Lisa’s smile has been the subject of countless works of art criticism, mostly because of the ambivalence that it suggests. Is she happy? Sad? Perplexed? It’s exactly the kind of delicious enigma that historians love to argue over and they will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Finally, and more prosaically, the Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911 and not recovered for a full two years – leading the world to believe one of its finest works of artistic heritage was lost forever. Luckily, it was recovered and today it basks in the sort of celebrity usually reserved for pop music stars and British royalty.

Today it is, hands down, the most popular thing to see at the Louvre. The only way to see it with any peace is to carefully time your visit to coincide with closing time when the crowds thin a bit—like we do at Walks on our Closing Time at the Louvre Tour.

FAQs about Louvre Must-Sees

Q: What are the must-see exhibits at the Louvre?

A: The top exhibits include the Venus de Milo, the Mona Lisa, and hidden treasures like Lamassu.

Q: How can I navigate the Louvre efficiently?

A: One of our top Louvre exhibit tips is to get to the museum as early as possible. Our second tip is to make a list of everything you want to see before you get to the museum. Once inside, grab a map and use our insider Louvre guide to plan out your visit.

Q: What historical insights does the Louvre offer?

A: The collections inside the Louvre museum provides deep historical context spanning thousands of years. From ancient Egypt and Islamic art to the Renaissance and the French Revolution, a trip to the Louvre is a walk through the history of every corner of the world.

Q: What are the best times to visit the Louvre?

A: Early mornings is always best to really cover ground, but the crowds tend to die down late in the afternoon as well. If you’d like a leisurely stroll versus a run through the collections, visiting the museum after 4 p.m. offers a quieter and more enjoyable experience

by Walks of Italy

View more by Walks ›Book a Tour

Pristine Sistine - The Chapel at its Best

€89

1794 reviews

Premium Colosseum Tour with Roman Forum Palatine Hill

€56

850 reviews

Pasta-Making Class: Cook, Dine Drink Wine with a Local Chef

€64

121 reviews

Crypts, Bones Catacombs: Underground Tour of Rome

€69

401 reviews

VIP Doge's Palace Secret Passages Tour

€79

18 reviews

Legendary Venice: St. Mark's Basilica, Terrace Doge's Palace

€69

286 reviews